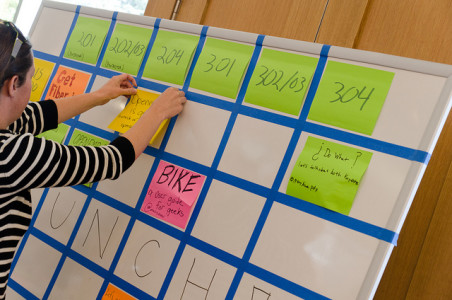

Because I'm the sort of person that takes pics: #PyDX pic.twitter.com/VbbKFY80s0

— social interaction (@brianwisti) October 10, 2015

We spent over a year planning PyDX. From my perspective, the result was worth every bit of stress. I’ve been thinking about what I want to say about the conference now that it’s over. I’ve stopped and started this post a dozen times so far. Several versions have been downright sappy.

Instead, here’s the top five things that stuck out for me during PyDX.

1. Bake Diversity in from the Start; It’s Not Something to Add Later

I have no shame when it comes to talking about diversity numbers in order to drum up sponsors, but I actually feel good about how we PyDX organizers handled questions of how to make our conference more diverse. We focused on what real people needed to feel comfortable showing up to a conference — providing a safe environment, offering child care, even small group opportunities.

- We came within four tickets of selling out.

- We provided full scholarships to more than 90 percent of applicants, and were able to offer free tickets to the rest through our volunteer program.

- We didn’t keep official numbers on diversity, but I made some informal counts. About half our attendees and speakers were diverse on some axis.

We didn’t have to focus on creating diversity when we already had a space that welcomed diversity in — and we responded directly to what people told us they needed to be able to attend. Remember, you can’t assume you know what anyone else needs.

Given that I attended a conference earlier this year that was exceedingly proud that 15 percent of attendees were women, I feel great about PyDX on this front.

2. Technical Talks Don’t Get All That Much Love, Surprisingly

I was obnoxiously proud of our speaker line-up, but I was surprised by what attendees responded to most enthusiastically. Looking at social media during the conference and talking to attendees afterwards, everyone was excited by talks that focused less on code — talks about topics like how to learn and how to build culture did really well.

The exceptions — the technical talks that got rave reviews — all had one of two key characteristics. Either they were workshops, where attendees participated and left with code of their own, or they were doing something far outside of typical Python projects, like making music,

Just about all of the talks went well, by the way. I’m not critiquing any of our speakers here. I’m speaking solely about what attendees were most excited by.

3. Not Screwing Up Codes of Conduct Requires Planning

I strongly believe that having a code of conduct is a minimum requirement for a conference (as well as smaller events and even occasional meetups). Having one sets expectations and creates a safer environment for every single attendee.

Organizing PyDX has only solidified my belief. The experience also highlighted some areas where we can make setting up and enforcing codes of conduct much easier — PyDX was a learning experience, because I’ve usually only been in a position to think about codes of conduct for smaller events.

These are my key takeaways:

- Create an incident response plan in advance. You never want to be trying to figure out how to deal with a specific issue in the moment, especially when you’re already stressed out of your mind about whether the keynote speaker’s laptop is going to work properly with the A/V equipment.

- Talk to an expert when creating your incident response plan. We actually didn’t write our own plan — instead, Audrey Eschright sat down with us and went over potential issues and how we wanted to handle them. She put that information together into a document we could refer to during the conference and that had enough detail that we could hand it to a volunteer if need be. Budget the money for that sort of expertise; it’s far cheaper than a lawyer after the fact.

- Every single organizer and volunteer is on duty for code of conduct issues. You should absolutely have a point person, but any attendee facing a problem will talk first with the staff member they most trust who they can catch alone. And those conversations are going to come up unexpectedly — no matter the events I’ve attended, restrooms are de facto meeting rooms because most people feel they can safely talk about anything there.

4. Venues Control So Many Things and They Could Use Their Power for Good

Our venue was our single largest expense. Our venue was also the most constraining factor in planning PyDX. Until we’d found a venue, we couldn’t figure out food, childcare, or even the actual dates of the conference.

First off, the UO White Stag Block was a great venue to work with. They were able to meet most of our requirements right away and there was really only one request we made that couldn’t be met, due to the classes that were in session in the building during our conference.

That said, any venue winds up controlling a lot of how a given conference runs. We had to work within our venue’s constraints:

- We could only use specific tape for hanging anything on the walls.

- We could only use catering that had already been approved by the building.

- We had to have insurance for the event.

That last constraint has kept me thinking: Insurance is required in order to fix any problem that occurs during the conference, including legal dilemmas. Why don’t venues have similar expectations for tools that mitigate risk, like codes of conduct? Isn’t requiring events to do more work to avoid any problems or negative attention more cost effective for venues?

5. The Amount of Help People Offer is Amazing

PyDX is truly a community conference. We had two larger sponsors: MailChimp and Anaconda, both of whom made a major difference in our ability to put on the conference. But around 80 percent of our funding came either directly from ticket sales or from local companies supporting the conference (including a lot of consultants and other small businesses!).

I feel like everyone I spoke to in the weeks leading up to PyDX offered to help in some way. The whole experience has been an important lesson in gratitude for me — a reminder that people will help if you just remember to ask. A few will even go out of their way to help without the request.

Thank you to everyone who made PyDX a reality.

And for those inquiring minds who want to know, we were four tickets short of selling out, so I’m not getting the tattoo. At least, I’m not getting it this year.